Choosing a sanitary valve is rarely about picking a “good” valve. It’s about choosing the right valve for how your line actually runs: what you’re moving, how often you clean, how you control flow, and what risk you can tolerate around contamination, downtime, and product loss.

This guide breaks down the main sanitary valve categories and the types of processes each is best suited for, plus a practical checklist you can use when specifying valves for new installs or replacements.

Start with the process, not the valve

Before comparing valve types, define the operating reality. A valve that performs well on a water-like product can struggle with a high-viscosity sauce. A valve that’s fine for occasional manual operation may not hold up to constant automated cycling.

- Product characteristics: viscosity, particulates, sugar or protein loading, foaming tendency, shear sensitivity (cultures, emulsions).

- Cleaning approach: CIP frequency, chemical exposure, temperature, and whether you steam-in-place (SIP) or need true drainability.

- Control needs: simple on/off, throttling, tight shutoff, frequent cycling, position feedback, or automation.

- Risk areas: cross-contamination concerns, allergen changeovers, and whether the valve sits in a “hard to clean” location.

- Utilities and limits: available air supply for actuators, max pressure/temperature, and pressure drop tolerance.

If you’re early in selection or replacing multiple valves across a system, it helps to browse valve families as a group so you can standardize where it makes sense. See the main sanitary valves category for common options.

Main sanitary valve categories and where they fit best

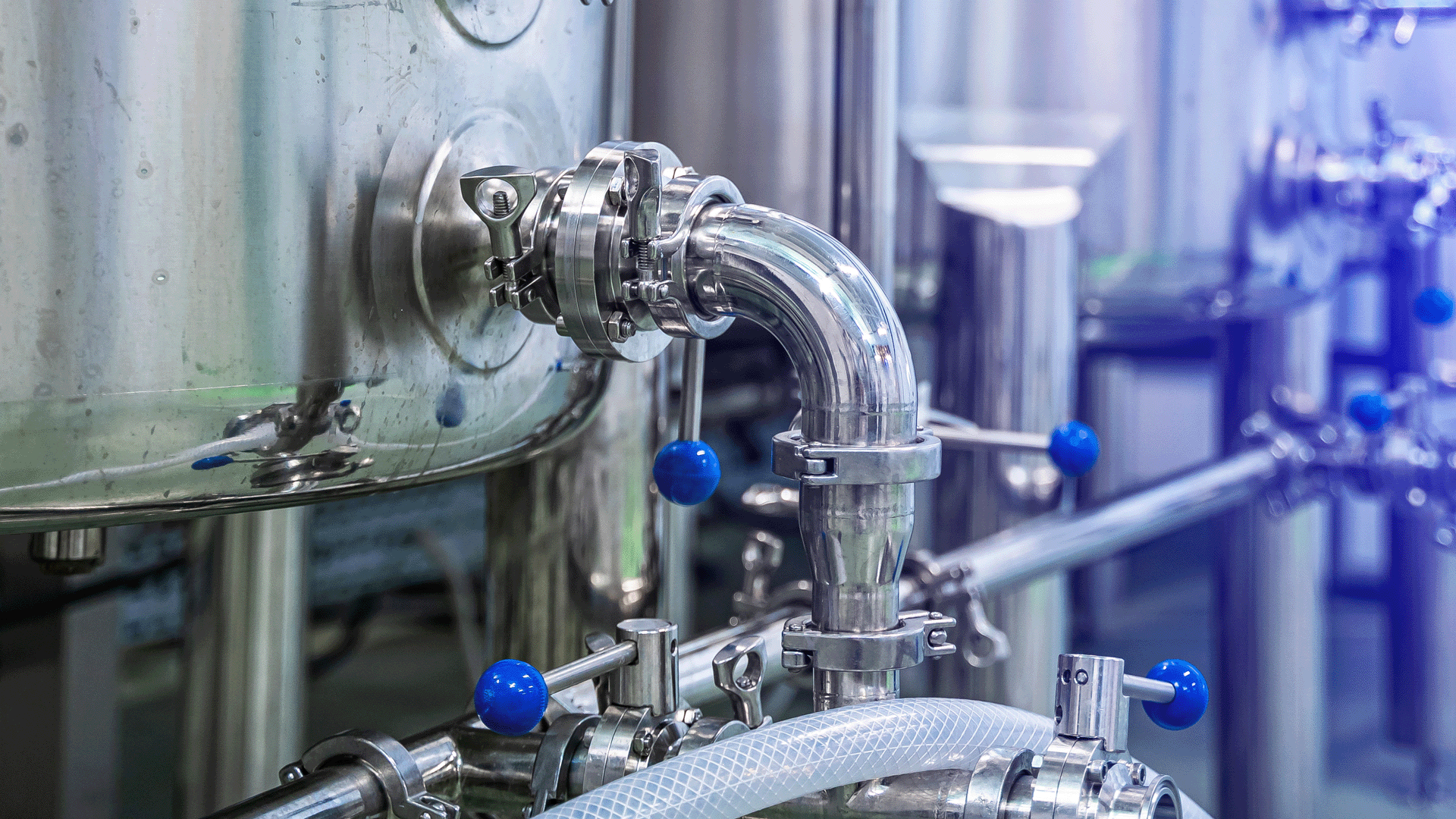

Butterfly valves

Best suited for: low-to-medium viscosity fluids, simple shutoff, and high flow with minimal cost and footprint.

- Common processes: water systems, CIP supply/return, breweries (wort/beer transfer), wineries (certain transfers), and general food and beverage utilities.

- Why they work: quick operation, easy to automate, compact, and widely standardized.

- Watch-outs: the disc sits in the flow path, which can increase turbulence and can trap certain products. Not ideal for heavy particulates or where maximum drainability is critical.

Ball valves

Best suited for: full-bore flow, thicker products, and applications where you want strong shutoff with relatively low pressure drop.

- Common processes: viscous food products (syrups, sauces), certain transfer lines where product recovery matters, and utility lines where full-port flow is desired.

- Why they work: good flow characteristics and strong isolation when properly selected.

- Watch-outs: not all ball valves are equally cleanable. In hygienic service, pay close attention to cavity design, seal interfaces, and whether the valve is truly intended for CIP/SIP duty.

Diaphragm valves

Best suited for: high-hygiene applications, frequent cleaning/sterilization, and lines where cleanability and separation from the actuator are major priorities.

- Common processes: pharmaceutical and biotech, aseptic or high-care food processes, WFI/clean utilities, buffer/media prep, and points of use where microbial control is critical.

- Why they work: the diaphragm creates a clean separation between the process and the actuator environment, with smooth internal geometry when specified correctly.

- Watch-outs: pressure drop can be higher than some alternatives, and diaphragm life depends on temperature, cycling, and chemistry. Stocking the right spares matters.

Check valves

Best suited for: backflow prevention, pump discharge protection, and maintaining directional flow without operator action.

- Common processes: downstream of sanitary pumps, CIP circuits (to protect chemical tanks), and any area where reverse flow could contaminate product or utilities.

- Why they work: automatic protection against reverse flow that can cause cross-contamination or equipment damage.

- Watch-outs: cracking pressure and valve style matter. The “right” check valve depends on orientation, flow profile, and whether you can tolerate water hammer.

Sample valves

Best suited for: hygienic sampling for QC/QA without opening the system.

- Common processes: dairy and beverage QA checks, fermentation monitoring, pharma in-process sampling, and any operation with routine lab testing.

- Why they work: designed to obtain representative samples while reducing contamination risk.

- Watch-outs: sampling points are only as hygienic as their cleaning practice. Sampling valves should be included in CIP procedures and inspection routines.

Match valve type to common process scenarios

High-flow transfer of low-viscosity product

If you’re moving a water-like product and you want a compact, economical valve that’s easy to automate, butterfly valves are often the first choice. This is common in beverage transfer, CIP routing, and general utility lines.

Thicker products and product recovery priorities

For viscous products where pressure drop and “hold-up” matter, a full-port ball valve is often considered. In these lines, think about cleanability, cavity design, and whether your CIP actually reaches the internal surfaces that will see product.

Shear-sensitive or high-hygiene, high-cleaning-frequency operations

In pharma/biotech and other high-hygiene environments, diaphragm valves are frequently used because they support hygienic design goals and can perform well under repeated cleaning and sterilization cycles when properly specified.

Preventing cross-contamination from backflow

Check valves are “quiet heroes” in sanitary systems. Place them where reverse flow could push product into a CIP line, chemical tank, or upstream vessel. Select style and cracking pressure for your flow rates and mounting orientation.

QA sampling without opening the line

Sample valves are purpose-built for routine sampling. They help reduce risk versus breaking a connection or adding temporary hardware, especially when sampling is frequent or documentation requirements are tight.

Don’t ignore materials, elastomers, and cleaning conditions

In sanitary processing, the valve body is only part of the story. Seats, diaphragms, and seals often drive real-world performance. Cleaning chemicals, temperature, and cycle frequency can shorten seal life or cause swelling, hardening, or loss of elasticity.

- Temperature: hot CIP and SIP push elastomers hard. Confirm continuous and peak ratings, not just “typical” conditions.

- Chemistry: caustic, acid, oxidizers, and sanitizers can attack certain compounds over time.

- Changeovers: if you run allergens or frequent product swaps, prioritize drainability and cleanability, and plan for seal inspection and replacement.

Manual vs actuated valves and what automation really changes

Automation adds consistency and speed, but it also changes what matters: cycle life, feedback signals, air quality, and maintenance planning become more important. If a valve will cycle constantly (for example, in automated CIP routing or batching), choose designs intended for high-cycle service and make sure maintenance access is realistic.

Also consider standardizing on a few valve families and actuator styles. It can simplify spares, training, and troubleshooting.

A practical specification checklist

- Valve type and size (with flow rate and allowable pressure drop)

- End connections and standards used in your plant (clamp, weld, etc.)

- Body material (commonly 316L in higher hygiene environments) and surface finish expectations

- Elastomer/diaphragm material matched to CIP/SIP temperature and chemistry

- Operating pressure and temperature, including cleaning and upset conditions

- Control requirements: on/off vs throttling, position feedback, fail-open/fail-closed

- Cleaning method: CIP coverage, drainability, and whether disassembly for inspection is expected

- Maintenance plan: seal kits, inspection intervals, and access constraints